As he recovers, a message arrives stating that Johanna will marry him after all. Rather than die, the plant just makes him sick. She rejects him, and Gauss tries to kill himself by ingesting the poison plant curare. Around the turn of the century, Gauss proposes to Johanna Osthoff. However, the later 20th-century work of Albert Einstein regarding relativity would serve as further confirmation of Gauss's suspicions that the universe was non-Euclidian. Rather, space is "folded, bent, and extremely strange." Fearing the controversy over questioning the fundamentals of Euclidian geometry, Gauss never publishes these findings they only survive through letters he writes to colleagues. Although surveying is initially a day job, something he considers unworthy of his immense talents, this work leads him to one of his most groundbreaking discoveries: that Euclid, the father of modern geometry, was wrong when he argued parallel lines never meet. When Gauss doesn't have his head in a book, he works as a land surveyor to keep from falling into poverty. When the two reach Ecuador, they climb Mount Chimborazo in the Andes, which at that time was thought by Europeans to be the highest peak in the world. While Bonpland seeks to have sex with virtually every woman they meet, Humboldt largely keeps to himself, doing diligent and quiet scientific work, such as scraping moss from cave walls to measure its dampness. On a stop in the Canary Islands on the way there, Humboldt must tear Bonpland off a naked native woman on Tenerife. While Gauss is huddled over mathematical equations and texts, Humboldt travels the world, departing on a trip to Central and South America in 1799 with his new friend and colleague, the French explorer and botanist Aime Bonpland. Some aspects of their construction seemed incomplete, occasionally hastily thought out, and more than once he thought he recognized roughly concealed mistakes-as if God has permitted Himself to be negligent and hoped nobody would notice." As Gauss works on the text, he considers whether what he is doing is sacrilegious: "At the base of laws there were numbers if one looked at them intently, one could recognize relationships between them, repulsions or attractions. By the time he is a teenager, he begins to make groundbreaking mathematical discoveries, and at the age of 21, he writes the Disquisitiones Arithmeticae, a fundamental text in the field of number theory whose influence persists to this day. Despite these humble beginnings, Gauss is a child prodigy who begins correcting adults' math mistakes at the age of three. Born in 1777, Gauss belongs to a poor working-class family and illiterate parents. By contrast, Gauss comes from wildly different circumstances. In 1796, the death of his stern mother for whom Humboldt has little affection allows him to pursue this dream. Over the next few years, he embarks on various geological and botanical tours financed by the state, but he dreams of traveling to the New World.

Groomed for greatness from an early age, Humboldt finds early success as a young scientist helping mining companies to increase their output. Born in 1769 in Prussia, Humboldt belongs to a prominent family of some wealth.

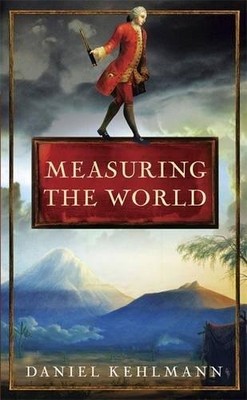

Although Gauss and Humboldt meet briefly in the first chapter at the 1828 German Scientific Congress in Berlin, the two characters spend most of the book apart, as the author flashes to each of their early lives then alternates between their stories in each chapter. The book was adapted into a film directed by Detlev Buck in 2012. German-Austrian author Daniel Kehlmann’s historical novel, Measuring the World (2005), offers a fictionalized account of the lives of the German mathematician Carl Friedrich Gauss and the German geographer Alexander von Humboldt, two figures who in the 19th century developed groundbreaking methods for measuring the Earth.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)